A few days ago I was talking with one of my friends who works for a large Internet company. A few months ago his team conducted a one-day workshop to find the most promising features which they could deliver to their users next year. So, he explained, we did everything by the book.

They met in a conference room far away from their regular office, set up charts, markers, sticky notes and started brainstorming. For him, it was an amazing experience. They had tons of ideas and wrote them all down on the wall. Then, they prioritized the features and chose the most important ones. Later on, they digitalized the work and, therefore, had an excellent to-do list. We were proud of ourselves and ready to start the work, he said.

Surprisingly, a few months later none of the remarkable features they wrote down made their way into production, so my friend asked: what did we miss? Where did we failed?

Visualization is not a silver bullet

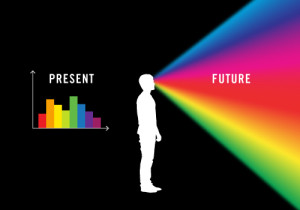

When I started listening, it all became clear. When they did the workshop, they naturally imagined themselves achieving newly defined goals and were proud of the work they did. “It will be so cool to have this in production — people will love it!” Unfortunately, psychological research suggests that this type of visualization alone is not the key to success, and it can, in fact, even hurt the future performance.

In a 2002 study, four researchers examined a few different scenarios: graduates looking for a job, undergraduates anticipating an exam, students having a crush on the opposite sex or patients undergoing hip-replacement surgery. Among these groups, people who had developed in their minds a vision of inevitable success, in fact, failed more often than people who were not overconfident about their future success.

How come? - my friend asked. I asked myself this, too. Sadly, there is no one single answer to the question of why this happens. However, a few possible explanations seem to be at the forefront.

Firstly, fantasizing about the future can devour our energy resources — the more you think about how wonderful the future will be, the fewer resources you have to make the change possible. Secondly, if we are overconfident about the future, we may pursue goals which are unfeasible and, therefore, waste much of our time by doing unnecessary work, which due to the “sunk cost fallacy” can refrain us further from changing our strategy.

Also, there is a third, not yet mentioned issue, which, I believe, causes more failures than others. However, before I write about this issue, let’s set aside psychology for a while and talk about business.

Definite versus Indefinite

Peter Thiel, a founder of PayPal and Palantir, in his latest book, “Zero to One”, paints a rather crude picture of the current state of entrepreneurship. He divides today’s businesses into four types based on two factors: belief in certainty about the future and the attitude towards it.

People can either welcome the future or fear it: this makes them either optimistic or pessimistic. However, according to Thiel’s theory, each optimist can also be either a definite or indefinite one.

“If you treat the future as something definite, it makes sense to understand it in advance and to work to shape it. However, if you expect an indefinite future ruled by randomness, you’ll give up on trying to master it.”

A definite optimist is a person who not only knows that the future will be better, but also has a plan for making it better. On the other hand, an indefinite optimist sees the future in bright colors but does not know how that will happen, so he does not make any concrete plans.

So, let’s get back to our little workshop.

During the workshop, my friend, and his team had rosy projections about the future. They were exhausted but happy with all the work that they did that day. However, they missed one essential point the next day. “Did you write down how you will deliver any of these features?; what is needed?; who can work on that and so on…?”

My friend just smiled. They had foreseen bright future but had not agreed on HOW they would make it come about.

Why we think we are making plans, but we are not

Peter Thiel devotes almost an entire chapter to discussing why indefinite optimism is so wrong, but how come, we keep thinking about our businesses, projects and life in general in this way?

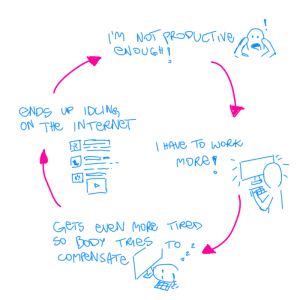

Personally, I believe that we are so engaged in the “future projection” process that we tend to overestimate our capabilities. My friend is not stupid, and neither are his teammates. During the workshop, they did not think “whatever will be, will be.” They were sure of their goals and thought that we would achieve them soon. The plans were fully developed in their minds.

Personally, I believe that we are so engaged in the “future projection” process that we tend to overestimate our capabilities. My friend is not stupid, and neither are his teammates. During the workshop, they did not think “whatever will be, will be.” They were sure of their goals and thought that we would achieve them soon. The plans were fully developed in their minds.

I work in the software development field, so I often hear complaints such as: “we want to change our process, but nothing ever actually changes — why?”, “we had an excellent plan but failed to deliver — why?” Very often the truest answer is the cruelest. You did not have a plan; you merely had a goal but did not work hard enough to determine how you would achieve it. You did make suggestions about how to change the process, but you never defined how you would make the change happen.

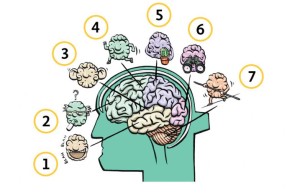

We think that we can just keep the entire plan in our heads. However, as many types of research suggest, our brain is simply not designed to hold such information without significant effort (or even at all). Most of our creative work happens in the part of the brain called the prefrontal cortex. As David Rock suggestively describes in his book “Brain at Work”, the capabilities of the prefrontal cortex are astonishing, but, at the same, incredibly energy consuming compared to older parts of the brain which are responsible for instincts, among other things. Rock paints the prefrontal cortex as a metaphorical stage which contains many actors representing different ideas. The issue is that the stage is small, and there is a limited space for new artists. Moreover, there can be only one scene playing on the stage at the same time. Setting aside the theatrical analogy, we can only focus on one non-habitual thing at a time.

Therefore, when we concentrate on the task at hand, we immediately lose sight of the bigger picture. When we switch our focus to the bigger picture, we lose the connection between it and our current work. It is like a continual struggle to strike a proper balance between now and the future.

Moreover, our brains are very smart. When they lack the energy resources to grasp the entire plan of execution, they create invisible shortcuts and abstractions. Unfortunately, they do this silently, without our explicit approval. Therefore, even when we think that we have managed to comprehend the entire picture correctly, in fact, our brain is continually filling in gaps without our knowledge, essentially making all our plans leaky.

How to help ourselves

So, as a species which evolved to chase animals on the savanna, are we doomed facing whiteboards with sticky-notes?

Not really. There are a few ways to make the process more efficient, but one is very simple and extremely helpful. First, we need to make the plan more visual and sonorous. Explicitly saying or drawing what we need to do step by step helps us to focus not only on the destination but also to concentrate on the journey in and of itself. Moreover, this is more than useful in striking a balance between positive empowerment and deceptive fantasizing. Then, we need to write down what we have just said or drawn in the form of simple, understandable and not too detailed steps.

The prefrontal cortex is not able to analyze more than few things at once. If we flood it with tons of little tasks, it will be far more exposed to distractions, and we will get tired sooner. Start with larger goals and only, later on, split them into smaller tasks. Now, we can add the most important dimension to our framework — the time.

The prefrontal cortex is not able to analyze more than few things at once. If we flood it with tons of little tasks, it will be far more exposed to distractions, and we will get tired sooner. Start with larger goals and only, later on, split them into smaller tasks. Now, we can add the most important dimension to our framework — the time.

There are many to-do list apps which proclaim that they can fix the planning issue for us. However, after trying many of them, I think that most of them miss one important point (which is why my friends and I created CayenneApps). They do an excellent job of helping you to clear your mind, but can quickly become junk drawers where we put everything with a single “to do” label.

If you want to make your plans doable, place the execution of your tasks in a particular point of time. I am not talking about setting a due date, but about setting a given day, or a particular hour when you will accomplish the task. A commitment such as “I will prepare materials for the marketing agency on Tuesday between 9 and 11 AM” is much more powerful than just saying that “I will prepare materials for the marketing agency.”

If I make plans to travel to the U.S. (which I currently am), I not only list what needs to happen beforehand — I also describe how I will make it happen and place all these smaller and bigger tasks on my calendar. Therefore, my prefrontal cortex no longer has to worry about these things.

Takeaways

Making commitments, mentioned above, may seem to give ourselves an unnecessary additional burdens. Undoubtedly, this may be difficult and you need a stronger will to develop it as a habit. However, this eventually pays off. As my friend and his team did, we tend to think that plans will evolve naturally from our goals if we focus on accomplishing them. Unfortunately, in most cases, they will not and we do need a concrete plan to move forward. Being optimist alone is not enough — as Peter Thiel would say, if we want to be successful in our work, projects or life we need to be more than that. We need to be definite optimists.

In the end, I prepared a quick sum up with a few things to remember:

- Visualizing achieving a goal alone can actually hinder the performance

- Fantasizing about success consumes energy resources, makes us less active and encourages us to avoid making plans

- Definite optimists not only welcome the future, but also make plans about how to make the future happen

- Indefinite optimists rely on luck

- Keeping plans only in the mind is not enough

- Due to limitations of the prefrontal cortex, people cannot focus both on everyday work and the bigger picture

- Making visual plans is very helpful and relieves the brain of unnecessary burdens

- Writing down a plan as a to-do list is useful, but it is not enough

- Placing parts of your plan on the calendar increases the chance of success

Takeaways:

- After defining a goal decide how you will achieve it and say it out loud, or make a drawing

- Define a list of necessary actions to achieve the goal

- Start with larger sub-goals, and only then move to more details

- Place the nearest tasks on the calendar to ensure their execution at a given point of time

- Track the progress and adjust the plan accordingly