“I hate to say I told you so, but have you all seen what customers are saying about our new ads? We should have chosen a different theme; the current campaign is a disaster!”, shouted Joe, one of the marketers on the new product team. A few people in the room sighed. “He is such a jerk”, thought Jenny, the main brain behind the new campaign theme.

A few minutes before, she was disappointed and sad — their new campaign had failed awfully, but with Joe’s comments she became angry and defensive. “I think we should have listened to Joe, he had pretty strong arguments”, said Helen, an analyst on the team. “Oh, c’mon Helen, we have discussed the theme over and over again until we finally reached a consensus!”, retorted Tom, one of the designers on the team. “Yeah, a great consensus when no one listens,” muttered Joe. “We all agreed that we are doing it this way!”, Jenny couldn’t restrain herself any longer and shouted loudly.

The marketing team, previously one of the best in the company, sank into a fierce argument. People who had known and trusted each other started to throw personal insults at one another. The good vibe which had previously driven the team’s productivity now dropped altogether.

What happened?

In the previous article, I wrote that having a team which trust each other is not enough. People not only have to like each other to perform well, but they also have to be ready to engage in serious and substantive conflicts to choose what is best for them. Nevertheless, having essential heated arguments is neither a silver bullet nor even a sign of a prospering and healthy team. What we need is a culture of listening and clarity, where people can buy-in and, despite differences of opinions, to eventually commit to decisions that have been made.

What we need is to get rid of another dysfunction of a team: the lack of commitment.

Have you ever had a similar situation to the one described at the beginning of the article? If not, then lucky you! If yes, welcome to the club of thousands and thousands of employees, community and family members who struggle with these kinds of disputes dozens and dozens of times in their lives.

To understand why these types of arguments even take place we must understand the fundamental dynamics of team discussions.

First, there is a decision to be made.

If the decision is trivial, very often the decision-making process goes smoothly — either the underlying decision factors are easily comprehensible, or the decision is so minor that no one cares whether the team makes it this way or another. The problem begins when the team wants to assess a more complex decision — one where the stakes are high.

Teams very often believe in decision-making rationality; and therefore want to perform a thorough analysis before making a choice. When people are engaged, analyses demonstrate differences among team members and conflicts emerge. When conflicts appear three possible things can happen:

1) analysis paralysis occurs;

2) artificial consensus is made;

3) team addresses the problem to the authority.

None of these outcomes is particularly healthy for high performing teams.

Analysis paralysis

Analysis paralysis happens when the team is unable to make a decision due to either an abundance of options in general or the existence of openly conflicting choices. This paradox of choice (described by Barry Schwartz) causes a cognitive pain, and may eventually lead to indecisiveness. Teams with analysis paralysis may become too conservative, consequently avoiding taking new paths and stopping growth. Overly conservative can lack innovation and therefore, are more prone to missing new opportunities.

Artificial consensus

When teams face openly conflicting choices, they can evolve into consensus-driven teams. In theory, a notion that each important decision of a team must be a result of a consensus sounds good, but in practice, it leads to a common problem which I call consensus-dilution.

When a decision cannot be made, people’s opinions are carefully diluted down to a point when ‘the consensus’ is made. Unfortunately, very often when two opposite opinions become diluted, we have a situation when everyone is equally unsatisfied. When one person prefers red, and another person prefers green, choosing yellow doesn’t help. The artificial consensus is a powder put on a bleeding wound, it may help for a while, but without disinfection, we may end up in a situation similar to the one with Joe and Jenny.

Authority-based decision

When teams become tired of analysis paralysis or false consensus they can resort to some kind of authority. Authority can be a manager in a company, a C-level executive, a community leader or when you are a child, your mom. Authority-based decisions are convenient because they ‘outsource’ the decision-making burden (and cognitive dissonance) away from the teams, therefore providing temporary relief. But at the same time, resorting to authority is short-sighted because it does not solve any of the underlying problems.

The command-and-control model, where the leader makes all important decisions, creates a bottleneck which may cause the same number of missed opportunities as analysis paralysis. It can disengage people because the decisions are no longer in their hands. It puts an additional burden on the already overloaded resource. And ultimately, what is the point of having self-organizing teams if most decisions are made someplace else anyways?

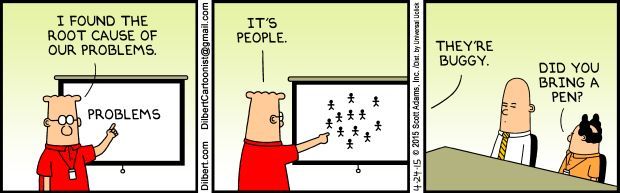

The root cause

If analysis paralysis, artificial consensus and authority-based decisions are all bad, what is the proper and efficient way to allow teams to make decisions more smoothly? Some people say that the only way is a hybrid approach: democratize some decisions by voting, authorize others by leader-based decision-making. These are useful tools, but they treat symptoms, not causes. If we want to vote for or against, we can still hurt some people that are a minority. If we delegate too many decisions to the leader, the leader may become too overwhelmed. What we need to do, is to heal the root causes.

Set the Golden Rule

First of all, we need to set the rules. There is a golden rule coined at Intel, which can be summarized as “Disagree and Commit”. When “disagree and commit” is in place, the situation described at the beginning of this article cannot happen. If the decision is made, everyone, even the people who disagreed, must follow the same goal. This is the rule. This is also the goal — we need to create a culture when the rule isn’t an empty slogan. So how can we create one?

Listen actively

Fortunately, human psychology is on our side. When people have an opinion, the biggest issue is not that their view did not directly influence the decision made. The core of this problem appears long before the decision-making process finishes. The most important thing is that one’s opinion has been carefully listened to, and noted. That’s all. This is very often as simple as just writing down people’s ideas without filtering them out beforehand. If each opinion has been evaluated by the whole team, the overwhelming majority of people will not want to revise the team’s decision later on.

When team members begin to become more aware and engage in active listening with their peers the probability of unessential conflicts will drop radically. When team members begin to use methods such as paraphrasing to understand other team members better, the clarity of the decisions made will increase, and the decision-making process will become more healthy.

Disconnect problems from people

In his great book describing the Pixar Animation Studio culture, Ed Catmull defines one of the main Pixar virtues as ‘being candid’. He writes about Braintrust meetings when various people from throughout the organization discuss early versions of their movies. Two key ideas make Braintrust work. The first one is openness, the second one is disconnecting people from problems.

If you want to make the decision quicker, break the connection between the idea in and of itself and its author. Let people discuss the problem without referring to ideas as Joe’s, Susan’s, Jenny’s ideas. If someone defines an idea, let another team member describe it to the rest of the team. When people disconnect from their idea they will be more eager to get over it when the team picks something different.

Summary

Patrick Lencioni also describes other methods which help teams to perform better. You can set clear deadlines to create clearer rules on how the decision-making process should proceed. You can perform a worst-case scenarios analysis to make cautious team members feel safer.

There are many tools, but to make them work, we should remember about one fundamental idea.

No matter how hard the team tries to make decisions quickly, no matter which tools the team uses, when the culture does not allow people to make mistakes the whole process will soon deteriorate. Each decision made by the team is a path chosen at crossroad, but to think that each path is chosen once and for all is dangerous.

Teams which perform admirably must have the essential ability to make bad decisions. As the Facebook motto says: we must “move fast and break things.” Without this mindset, each and every team will eventually become dysfunctional. With the ability to make bad decisions teams will be able to learn, recover and perform better than ever!